"I don’t know what I’m feeling”: working with alexithymia

... Part 7 of the Fundamentals of CBT series

Photo by Uday Mittal on Unsplash

In Part 6, we looked at how emotional dysregulation can make standard CBT hard to access for ADHDers. One of the biggest reasons? We often don’t even know what we’re feeling in the first place.

This brings us to alexithymia - a common but often overlooked trait that can make emotional awareness feel like a foreign language.

Alexithymia is a topic that even many therapists don’t know about, but it affects up to 40% of ADHDers - so I make no apologies for this being a meaty and lengthy article.

But if it’s too long, and you probably won’t read it, here’s the content in brief - dive in to the rest when you’re ready.

📌 TL;DR - what this article covers

If you struggle to name your emotions, feel flooded without knowing why, or often default to describing situations instead of feelings, you might be experiencing alexithymia - a common trait in ADHD that makes emotional awareness feel out of reach. This article explains what alexithymia is, how it links to interoception (your internal emotional radar), and why it matters for therapy. You'll also get simple, neurodivergent-friendly tools to build emotional awareness and make CBT more accessible - starting with just noticing whether what you feel is pleasant or unpleasant.

What is alexithymia?

Alexithymia literally means “no words for emotions.” People with alexithymia struggle to experience and process their emotions (Taylor, Bagby, & Barker, 1997).

Alexithymia is characterised by three factors:

difficulty identifying feelings

difficulty describing feelings

a tendency to relate emotions to external events, rather than internal experience

The first two are affect-related - problems with emotional awareness and expression. The third is a cognitive style called externally oriented thinking - avoiding internal emotional reflection and focusing on external circumstances instead.

Research increasingly shows that these challenges are underpinned by something more fundamental: impaired interoception.

What is interoception?

Interoception is your ability to sense internal bodily signals - like your heartbeat, hunger, muscle tension, and (crucially) your emotions. We recognise our emotions in part because of how they feel in our bodies. So if your interoception is impaired, your ability to identify and describe feelings will be too. You’re more likely to rely on external cues - like facial expressions or others’ reactions - to make sense of what’s going on inside.

People with alexithymia often have to intellectually guess what they’re feeling (e.g. “I suppose I must be angry”) instead of sensing it directly. This is where the concept of being “hangry” comes from - not realising you’re hungry until you’re snapping at someone.

What’s the link between alexithymia and interoception?

Studies show that:

alexithymia scores correlate with poor heartbeat perception - suggesting reduced access to real-time emotional signals. (Herbert et al, 2011)

people with high alexithymia show structural and functional differences in key interoceptive brain areas (Brewer, Murphy & Bird, 2021)

alexithymia may primarily be a disorder of interoception, not just of language or insight (Brewer, Cook, & Bird, 2016).

This reframes alexithymia from “I can’t put it into words” to “I don’t even get a clear signal to start with”

What alexithymia isn’t

It’s not a lack of feelings. People with alexithymia can still have:

Emotional depth

Empathy

Emotional intelligence - just not always in the conventional, verbalised way

In fact, alexithymic individuals often experience more empathic distress when confronted with others’ emotions. That’s not because they’re more empathic, but because they struggle to differentiate others’ feelings from their own. This can create a paradox: being highly attuned to other people’s emotions while feeling confused by your own.

This is known in the literature as empathic distress - an aversive, unpleasant, self-focused emotional response to others’ distress. It’s different from compassion, and it’s not uncommon in neurodivergent individuals.

Alexithymia isn’t a disorder or diagnosis. It’s a personality trait that often co-occurs with conditions like ADHD and autism.

What other conditions is alexithymia linked with?

It’s also associated with:

PTSD

Depression and anxiety

Fibromyalgia

IBS and migraine

Substance misuse and behavioural addictions

Traumatic brain injury and neurological conditions like Parkinson’s

It’s highly likely there are genetic factors, but it’s also linked with childhood adversity, especially emotional neglect.

Brain areas involved in emotional awareness

Several brain systems need to work together for emotional self-awareness:

Insula & anterior cingulate cortex - monitor internal states (interoception)

Amygdala & limbic system - assign emotional valence (is this pleasant/unpleasant)

Prefrontal cortex - label and reflect on emotions

If there’s disruption to any of these systems - structurally, chemically, or in terms of connectivity - your emotional radar becomes fuzzy.

Clues that you might be experiencing alexithymia

You feel overwhelmed or flooded, but can’t explain why

You often feel “nothing” but sense something’s going on underneath

You struggle to tell emotions apart — is this sadness, guilt, or shame?

You avoid emotional conversations or feel uneasy with others’ feelings

You attribute your decisions to events or bodily states rather than emotions

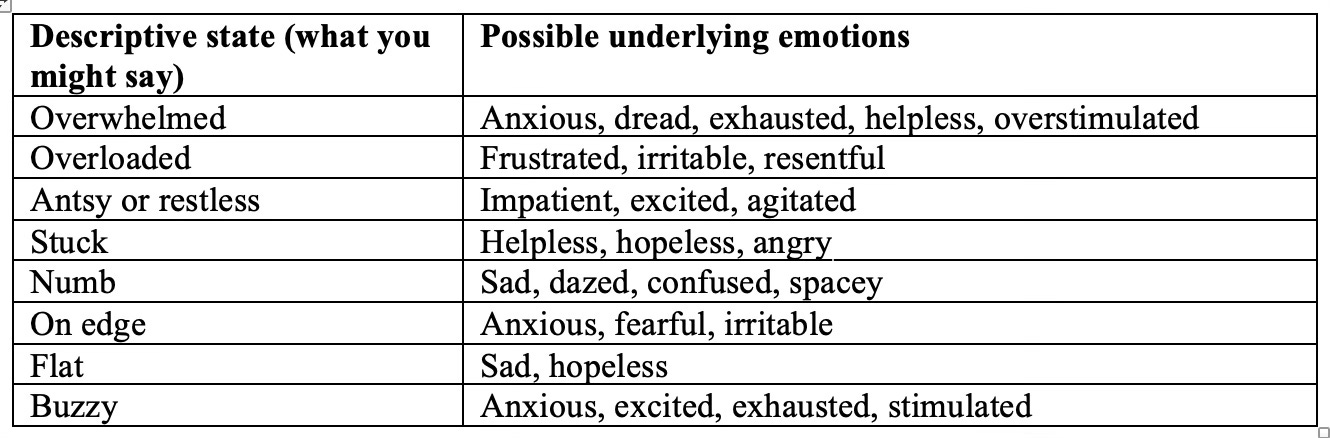

You describe states not emotions (“It was stressful” vs. “I felt anxious”). There is a subtle difference between a state and an emotion - the table below offers a translation from state to emotion.

If this sounds like you: you're not alone, and you're not broken. You’re just working with an emotional system that needs a different entry point.

Can you be tested for alexithymia?

There’s no formal diagnosis because alexithymia is a trait, not a disorder.

🧠 But there is a self-report tool: the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS). It’s free and available online and a helpful place to begin.

ADHD and alexithymia: what’s the link?

ADHD affects attention, motivation, and emotional regulation. Alexithymia affects emotional awareness and expression. They’re different - but when they co-occur, the emotional load can feel enormous.

People with both ADHD and alexithymia are more likely to experience:

Emotional outbursts or shutdowns

Greater impulsivity

Higher risk of anxiety and depression

Difficulty making decisions

A pressing need for support with emotional overwhelm

Why emotion identification matters for ADHDers

CBT relies on knowing what you’re feeling so you can challenge the thoughts that follow. But if you can’t name the emotion because alexithymia is also in the mix, the tools fall flat. That’s not a failure in you - it’s not your fault. It’s just part of how ADHD works for some of us.

Pausing to name a feeling doesn’t make it go away. But it gives you distance. And distance gives you options. And options are power.

When we name emotions, the amygdala calms down and the prefrontal cortex kicks back in. Naming really does help tame.

That’s why emotion recognition is a core element of the Soothing Pathway in my Enhanced CBT Model. It’s foundational work - often the first thing we need to address.

Working with alexithymia: tools and techniques

Based on the work of Dr Megan Anna Neff, a psychologist with lived experience of being Autistic-ADHD (neurodivergentinsights.com)

🔶 1. The Arousal-Valence Matrix

A simple grid mapping two key dimensions of emotion:

Arousal: how activated or subdued does your nervous system feel?

Valence: does it feel pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral?

In psychology, this is called valence. In Buddhist practice, it's known as vedanā or feeling-tone - the immediate, pre-thought sense of pleasantness or unpleasantness.

Feeling-tones are like the subtle background ‘colour’ that tinges every moment of experience. It’s the body and mind’s immediate read-out, registering whether something feels pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral - before any specific emotion or thought arises.

Image taken from Dr Megan Neff’s website

How to use it:

Ask: is my body energy high or low?

Ask: does this emotion feel pleasant or unpleasant?

Place an X in the quadrant that fits.

If you can, name the emotion

Based on the quadrant, choose a self-soothing or energising activity.

if you’re feeling high arousal and low valence, you might try deep breathing or other relaxation techniques intended to down-regulate and lower the intensity of the emotion.

if you feel low arousal and low valence, you might engage in an activity that will increase your energy and positive mood, such as movement, gentle stretches or listening to upbeat music, or spending time in a special interest.

💡 The Arousal-Valence Matrix helps you practice all three domains of alexithymia: noticing (interoception), recognising (valence), and naming (cognitive work).

⭐ 2. Using feeling-tone if specific emotions are too difficult to identify

If you can’t name an emotion yet, just notice the feeling-tone — pleasant or unpleasant. That alone builds emotional literacy. Then you can place it on the Arousal–Valence Matrix.

🧭 Ask yourself: Does this feel pleasant or unpleasant?

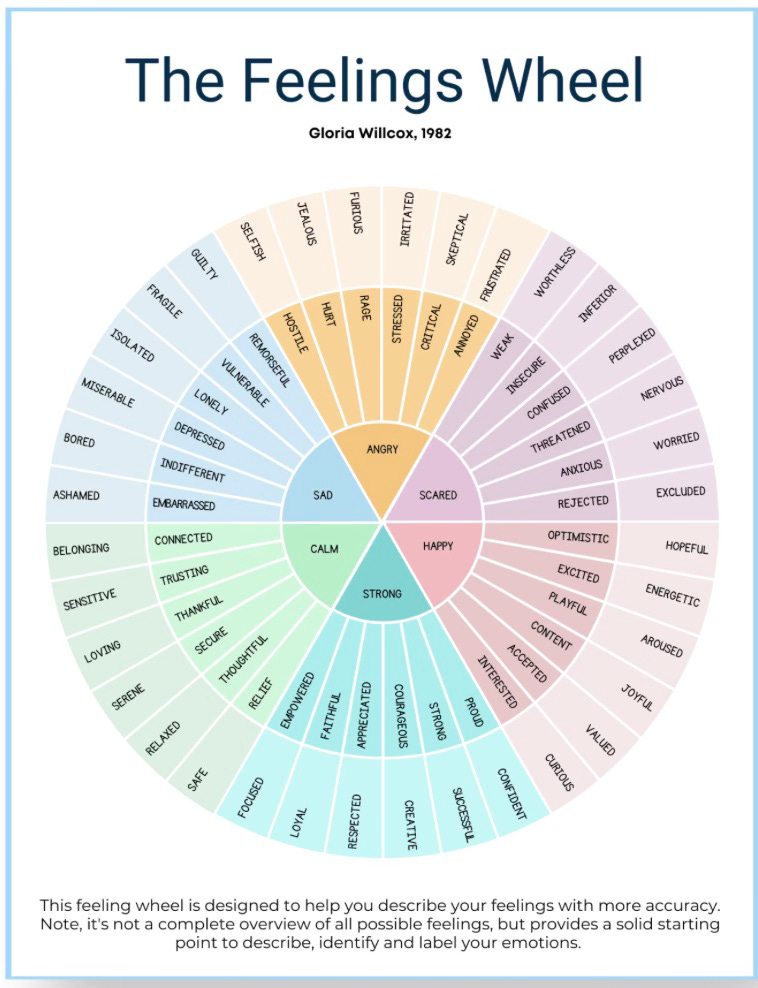

🌀3. The Feelings Wheel: expanding emotional vocabulary

A visual tool to expand your emotional vocabulary.

Image taken from Dr Megan Neff’s website

How to use it:

Start in the centre with a core emotion

Explore outward for nuance (e.g., angry → irritable)

Look at the opposite emotion to gain insight into unmet needs

Use that insight to guide action (e.g., if powerless → do something empowering)

🛠️ This is great for people who mainly have “mad, sad, fine” as emotional words.

Dr Neff also describes a Feelings List, very similar to the Wheel above.

🔺4. The Feelings Gauge

The Feelings Gauge adds intensity.

Image taken from Dr Megan Neff’s website

Rate emotions from 0–10. Most people with alexithymia only notice emotions when they’re at 8, 9 or 10, when the amygdala is already hijacked.

How to use it:

Use a traffic light system (green–amber–red)

Learn your own early warning signs at amber = score of 4-7

Learn your own late signs at red = 8-10

Track recurring thought, sensation and behaviour patterns

I’ve demonstrated this technique on myself in earlier posts on emotional overload and overwhelm - take a look at the vicious cycle formulations in this post.

💡 Over time, this helps you recognise emotional build-up earlier, before overwhelm hits.

🌱 5. Everyday practices for emotional awareness

Dr Neff also recommends:

Novels – track characters’ feelings and reactions

Music – use songs to evoke and identify feelings

Photos – name the emotions they bring up

Daily check-ins – ask: what’s happening in my body? What might I be feeling?

Journalling – jot down 3 emotions each day

Mindfulness – gently notice emotional cues, without judgment

These aren’t quick fixes. They’re slow, steady skill-building, like learning a new language.

Summary

Alexithymia can make your emotions feel like they’re written in invisible ink. But that doesn’t mean you can’t learn to read them.

For ADHDers, identifying feelings is often the missing step before CBT becomes effective. That’s why it’s a key part of the Soothing Pathway in my Enhanced CBT Model. When the thinking mind isn’t available, the emotional body needs to lead.

Call to action

If this article resonates with you, this is the main practice I’d encourage you to try this week:

Just try noticing: does this feel pleasant or unpleasant?

Optional extra actions you could take:

Take the Toronto Alexithymia Scale questionnaire

Plot a feeling or feeling-tone on the Arousal–Valence Matrix

Use the Feelings Wheel to find a more precise word

Track one emotion across a 0–10 scale

Name 3 feelings you had today (in your phone or journal)

Remember: not knowing what you feel isn’t a failure - the act of trying to notice is the skill.

Subscribe here - it’s all free, now and always.

Get more of what you want and less of what you don’t - manage your Substack experience by clicking here.

This is such a great article. So important and educative with so many good pointers for the neurodivergent community.